Because the Emerald Isle’s history is rich and complex, stretching back thousands of years, it is difficult to give a brief history of Ireland. But, in this article, I am going to try to do just that, as I have had many people ask me for a short rundown of the country’s history.

This brief history of Ireland is a very condensed one, with just the key events and milestones briefly discussed.

It is by no means a complete timeline and there is so much more to the history of this tiny island, but this should give you a general idea of how the island of Ireland has been shaped throughout the ages.

Introduction

The island of Ireland has been home to ancient cultures, including the Celts, whose influence remains evident in the country’s language and traditions.

From the Norman invasions in the 12th century to the struggle for independence in the 20th century, Ireland’s past is marked by resilience and a strong sense of identity.

Ireland saw significant changes during the Middle Ages, with the arrival of Christianity and the subsequent establishment of monasteries that became centres of learning and culture.

The island was also heavily impacted by English and later British rule, leading to notable events such as the Great Famine in the 19th century, which had devastating effects on the population and led to mass emigration.

The 20th century was marked by the Easter Rising of 1916 and the subsequent War of Independence, resulting in the partition of Ireland and the creation of the Republic of Ireland in 1949.

The peace process in Northern Ireland, culminating in the Good Friday Agreement of 1998, has been crucial in shaping contemporary Ireland.

In this article, you will learn a bit more about these events and their role in creating the Ireland we know and love today.

Early Inhabitants and Gaelic Ireland

As mentioned, Ireland’s history spans thousands of years, beginning with its earliest settlers and evolving through the rich Gaelic culture. Key historical periods include the Neolithic era, the influence of the Celts, and the advent of Christianisation and monastic culture.

Neolithic Period

The arrival of humans in Ireland can be traced back to approximately 10,000 BC. During the Neolithic period, around 4000 to 2500 BC, the island saw significant developments in agriculture and society. The inhabitants began farming, which marked a shift from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle.

This era also witnessed the construction of impressive megalithic structures. Newgrange, a famed passage tomb, is a prime example. These constructions reflect advanced engineering skills and a deep spiritual and communal life among the early Irish peoples.

Celtic Influences and Society

Around 500 BC, the Celts arrived in Ireland, introducing a new language, culture, and social structure.

The Celtic influence marked a transformative period with the establishment of clans, each governed by chieftains. Their society was hierarchical yet built on rich traditions.

Celtic art and mythology flourished, with intricate designs and epic tales becoming central to their identity. The introduction of iron tools and weapons also advanced agriculture and warfare, deeply intertwining with their daily lives and societal organisation.

Christianisation and Monastic Culture

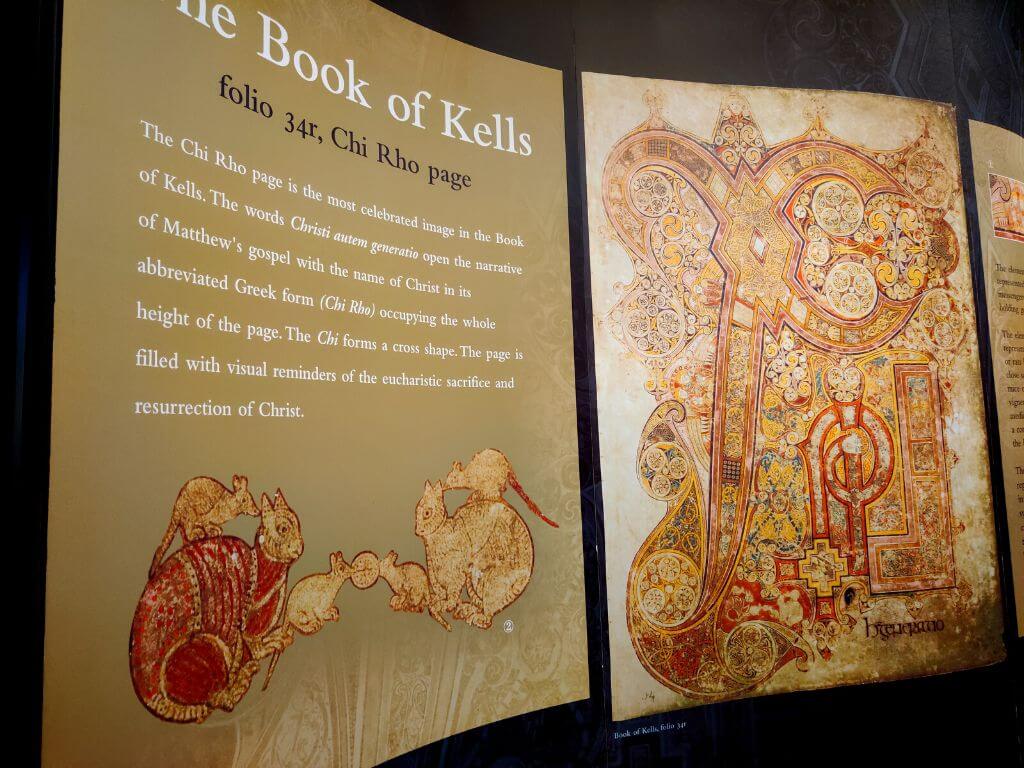

The advent of Christianisation began in the 5th century with figures like St. Patrick playing pivotal roles. This period saw the establishment of numerous monasteries, which became centres of learning and religious life.

Monastic culture produced some of Ireland’s most renowned artefacts, such as illuminated manuscripts like the Book of Kells. These monasteries not only acted as religious hubs but also preserved and advanced knowledge, art, and culture during this transformative time.

Viking Invasions and Norman Conquest

The Viking and Norman invasions significantly shaped Ireland’s history, impacting its political landscape and cultural development. These invasions led to new settlements and shifts in governance.

Viking Raids and Settlements

The Vikings began their raids on Ireland in the late 8th century, targeting monasteries and coastal communities. These raids, driven by the Vikings’ seafaring expertise, marked the beginning of a turbulent period with numerous attacks on Irish territories.

By the 9th century, Vikings established significant settlements along the coast.

Dublin, founded by the Vikings in 841 AD, became a major Norse city and a crucial centre for trade and administration. Other important Viking towns included Waterford (Ireland’s first city), Cork, and Limerick.

The Vikings’ presence influenced Irish culture and commerce, introducing new trade routes and goods. Despite their integration into Irish society, clashes between Vikings and native Irish lords persisted, leading to a complex dynamic of alliance and conflict.

Norman Invasion and the Lordship of Ireland

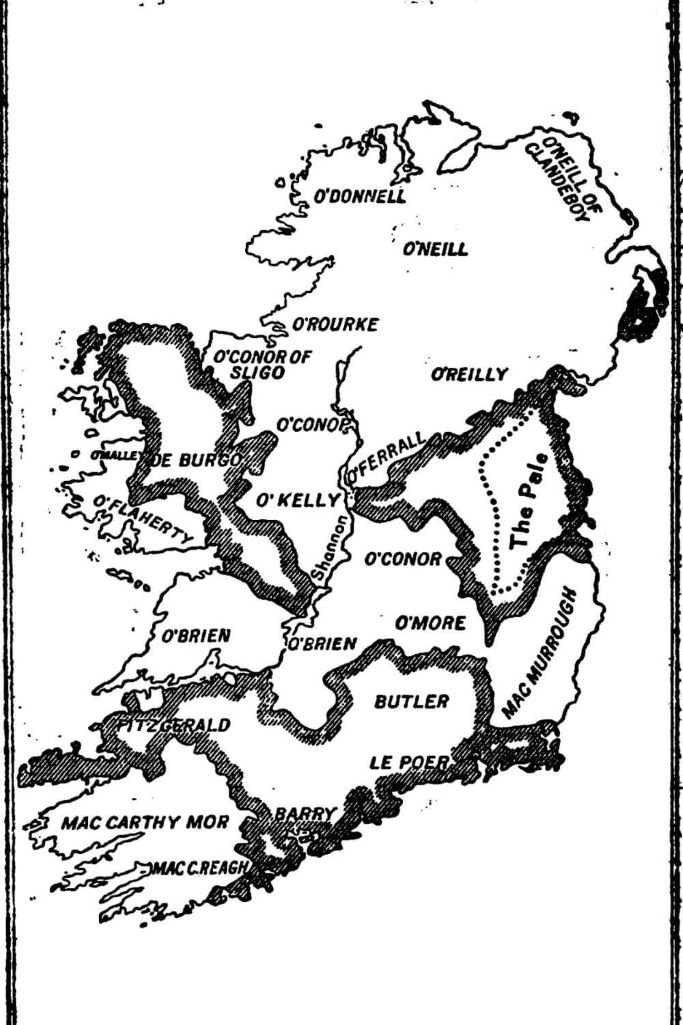

The Norman invasion began in the 12th century, initiated by Richard de Clare, known as Strongbow.

Invited by the ousted King of Leinster, Diarmait Mac Murchada, Strongbow’s arrival in 1169 marked the start of Norman involvement in Ireland.

The Normans brought advanced military technology and tactics, leading to their swift conquest of key regions. By 1171, King Henry II of England declared himself Lord of Ireland, establishing a feudal system that altered land ownership and governance.

The Norman influence extended beyond the battlefield, impacting architecture, law, and administration. They constructed stone castles and monasteries, leaving a lasting architectural legacy. Their legal systems and governance structures profoundly shaped the development of Irish society.

Despite resistance from Gaelic Irish lords, the Normans maintained control, laying the groundwork for future English dominance in Ireland.

English Rule and Irish Struggle

The period of English rule over Ireland saw significant conflict and transformation. Key events such as the Tudor Conquest, religious disputes, rebellions, and the Great Famine shaped Ireland’s history dramatically.

Tudor Conquest of Ireland

The 16th century marked the beginning of the Tudor Conquest, with England expanding its control over Ireland. Henry VIII declared himself King of Ireland in 1541, initiating direct English governance.

Throughout this period, numerous military campaigns were launched to subdue Irish lords and incorporate them into the English system.

The policy of surrender and regrant aimed to replace Gaelic norms with English customs. The most notable conflict during this era was the Nine Years’ War (1594-1603), led by Hugh O’Neill, resulting in a bitter defeat for the Irish.

Religious Conflicts and the Penal Laws

Religious tensions intensified post-Reformation as England enforced Protestantism. The Protestant Ascendancy emerged, dominating Irish politics and land ownership.

The Penal Laws, introduced from the late 17th to early 18th centuries, aimed to disenfranchise Irish Catholics and non-Anglican Protestants.

These laws included:

- Restrictions on Catholic worship and education

- Property laws restricting land transmission to Catholics

- Prohibition of Catholics studying abroad

- Prohibition of Roman Catholics from voting in parliamentary elections or holding office

The discriminatory measures led to widespread resentment among the Catholic majority and solidified sectarian divides.

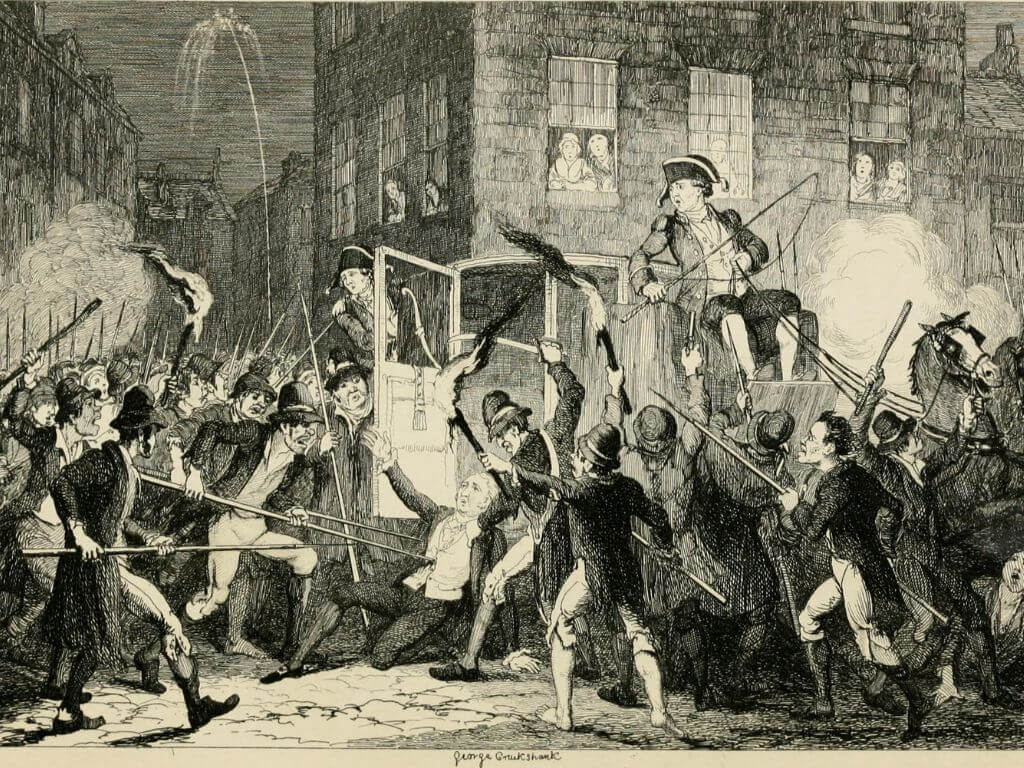

The Irish Rebellion of 1798

Instigated by the Society of United Irishmen, the 1798 Rebellion sought to end British dominance and establish an independent Irish republic.

Influenced by the American and French revolutions, the United Irishmen pursued a vision of an inclusive republic.

The rebellion spread across the country, particularly in Ulster and Wexford. Despite initial successes, the insurgents eventually faced decisive defeat. Thousands were killed, and the rebellion further led to harsher repressive measures from the British government.

The Act of Union and the Great Famine

The Act of Union in 1801 merged the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain to form the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. This legislative union dissolved the Irish Parliament, consolidating governance under Westminster, but did little to quell unrest.

From 1845 to 1852, the Great Famine struck following a potato blight. The primary food source for many peasants, the blight caused widespread starvation and disease. The famine resulted in roughly one million deaths and triggered mass emigration, particularly to the United States and Britain.

This catastrophic event profoundly impacted Ireland’s socio-economic fabric, leading to demographic shifts and intensified calls for independence.

Path to Independence

The journey to Irish independence was marked by significant political movements, uprisings, and pivotal treaties. These events shaped modern Ireland and defined its struggle for sovereignty.

Home Rule Movement

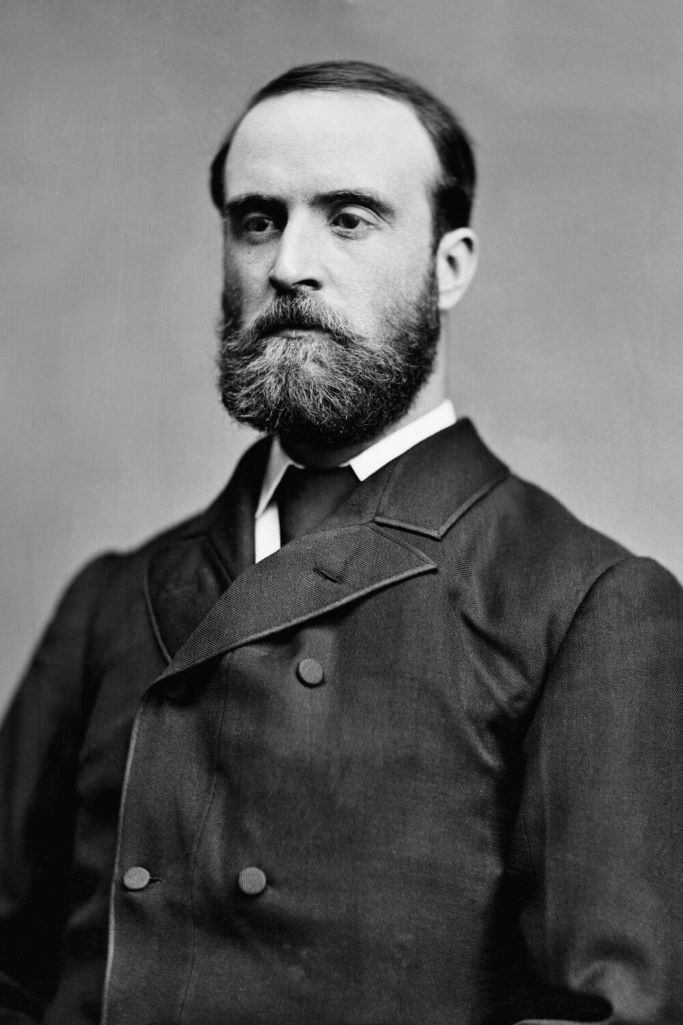

The Home Rule Movement emerged in the late 19th century as a political push for greater autonomy within the United Kingdom.

Spearheaded by Charles Stewart Parnell (pictured below), the movement sought the establishment of a separate parliament for Ireland. Despite initial successes, including the passing of two Home Rule Bills in the House of Commons, resistance in the House of Lords stalled progress.

The cultural revival during this period also played a crucial role in fostering a distinct Irish identity, aiding political efforts. Organisations like the Gaelic League promoted Irish language and culture, bolstering national sentiment.

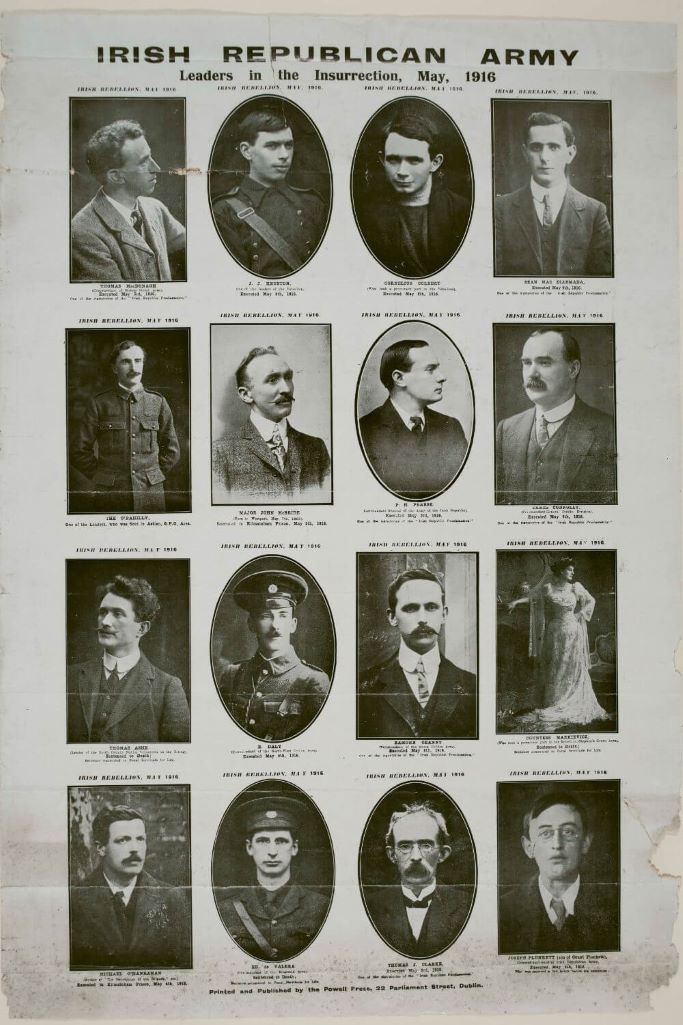

Easter Rising and the Irish War of Independence

In 1916, the Easter Rising represented a significant escalation in the fight for independence. Led by figures such as Patrick Pearse and James Connolly, rebels seized key locations in Dublin. Although the uprising was suppressed within a week, it shifted public opinion and increased support for independence.

The Irish War of Independence commenced in 1919, following the 1918 general election in which Sinn Féin won a landslide victory. The conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces involved guerrilla warfare and political manoeuvring.

By 1921, the intensifying violence and international pressure led to negotiations between Britain and Irish leaders.

Anglo-Irish Treaty and Civil War

The Anglo-Irish Treaty, signed in December 1921, was a landmark agreement that ended the War of Independence. The treaty established the Irish Free State as a self-governing dominion within the British Commonwealth.

Key figures in the negotiations included Michael Collins (pictured) and Arthur Griffith, who faced intense scrutiny and opposition for the compromises made.

The treaty’s terms, particularly the oath of allegiance to the British Crown, sparked a civil war between pro-treaty and anti-treaty factions. The conflict from 1922 to 1923 resulted in deep divisions within Irish society. Eventually, the pro-treaty forces triumphed, cementing the foundation of the Irish Free State.

The Republic of Ireland and the Troubles

The Republic of Ireland was formally established as an independent nation separate from the British Empire. Meanwhile, Northern Ireland experienced decades of conflict known as the Troubles, which concluded with the Good Friday Agreement.

Establishment of the Republic

Ireland gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1922, initially as the Irish Free State. In 1949, the country was declared a republic through the Republic of Ireland Act, severing all ties with the British monarchy.

Eamon de Valera, a key figure in the struggle for independence, played a crucial role in shaping the new republic.

The move to full republicanism was seen as a fulfilment of Ireland’s long-sought self-determination. The Republic of Ireland became a member of the United Nations in 1955 and later joined the European Economic Community in 1973.

The Northern Ireland Conflict

The Troubles, a violent conflict, began in the late 1960s in Northern Ireland.

It involved Republican paramilitaries seeking unification with Ireland, Loyalist paramilitaries wanting to remain in the UK, and the British state. Tensions grew over political representation, civil rights abuses, and religious divisions.

Key events included Bloody Sunday in 1972, where British soldiers shot unarmed protesters, and the hunger strikes in the early 1980s led by Bobby Sands. Violence resulted in thousands of deaths and significant social upheaval, deeply impacting Northern Ireland’s daily life.

Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement, signed in 1998, was a major political development.

It established a devolved government for Northern Ireland, requiring cooperation between Unionist and Nationalist parties. The agreement was endorsed by referendums in both Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Key provisions included the decommissioning of paramilitary weapons, the release of political prisoners, and the establishment of the North-South Ministerial Council to foster cooperation between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

The agreement marked a significant step towards peace, though challenges and political disagreements persist.

Modern Ireland

Modern Ireland has seen significant economic growth followed by new challenges in the 21st century. The country’s evolution is marked by a blend of economic transformation and cultural resurgence.

Celtic Tiger Economic Boom

Ireland’s economy experienced rapid growth during the 1990s and early 2000s, a period known as the Celtic Tiger.

Key drivers of this boom included foreign direct investment, particularly from technology firms, and a favourable tax regime. Unemployment rates fell dramatically, and standards of living improved for many citizens.

Key points:

- GDP growth rates were among the highest in Europe.

- Investments in education and infrastructure contributed to sustainable development.

- The housing market expanded significantly, leading to increased construction.

While this period brought prosperity, it also laid the groundwork for economic disparities and housing market vulnerabilities.

21st Century Challenges and Developments

Following the global financial crisis of 2008, Ireland faced substantial economic challenges. Recovery efforts included austerity measures and international bailouts.

The country has since worked to stabilise its economy, focusing on sustainable growth and technological innovation.

Key developments:

- Emphasis on renewable energy sources to combat climate change.

- Adjusting to Brexit and its impact on trade relations.

- Addressing social issues such as homelessness and healthcare reform.

These efforts highlight Ireland’s resilience and ongoing commitment to progress amid global and domestic challenges.

Conclusion

Ireland’s history is a tapestry woven with rich cultural traditions, fierce struggles, and significant transformations.

The island’s early Celtic roots and the influence of Viking and Norman invasions shaped its medieval identity.

The English and later British dominations introduced centuries of conflict and rebellion. The Great Famine in the 19th century was a devastating period, resulting in a massive population decline and increased emigration.

The struggle for independence in the 20th century led to the creation of the Republic of Ireland in 1949, while Northern Ireland remained part of the United Kingdom, leading to further political complexities.

Ireland’s modern era is marked by economic growth, cultural resurgence, and an evolving relationship with both the United Kingdom and the European Union.

Today, Ireland stands as a nation proud of its heritage and optimistic about its future. What remains to be seen is whether there will, one day, be a united Ireland.

You might also enjoy reading:

- What is the Difference Between Ireland and Northern Ireland?

- Things to Know Before You Go to Ireland

- Interesting Facts About Ireland

- Things Not to Do in Ireland as a Tourist

- The Two Capital Cities of Ireland

Save for later